The world’s oldest crystals show evidence of exposure to fresh and salt water during their formation, a new study reports. This shows that the very early Earth had both oceans and land on which rainwater could collect. Although diabolical in many ways, it suggests a planet far more similar to the one we know today than anything else in the Solar System, and the possibility for life to evolve.

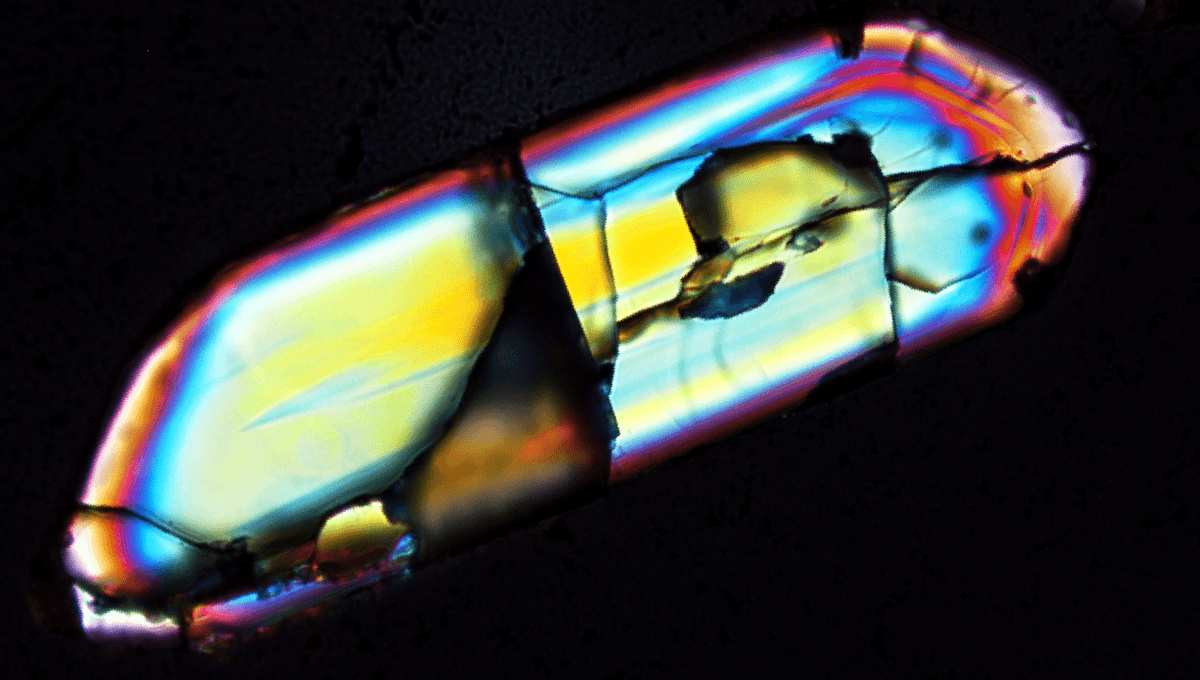

Most of the relics of early Earth have long since been recycled through the mantle, leaving nothing to investigate. The Jack Hills in Western Australia hold zircon crystals up to 4.4 billion years old. They are small and bound in much younger sedimentary rocks, but these are the oldest minerals on the planet and provide crucial clues about the state of the Earth when they formed.

Many zircons show evidence of having formed in water, and the type of oxygen within them reveals the nature of that water. Oceans contain water formed mainly from oxygen-16 atoms, but also with a little oxygen-18. “When water evaporates, oxygen-16 evaporates more,” Curtin University’s Dr Hugo Olierook told IFLScience, as it’s easier for the lighter molecules to escape. “Controlled mainly by temperatures, closer to the poles it becomes even lighter.” When the vaporized molecules fall as rain, the resulting lakes have reduced abundance of oxygen-18.

Billions of years later, Olierook is part of a team that has read the type of water in which the zircons formed from their isotope ratio. The vast majority of the Jack Hills zircons the team studied formed either inside the Earth, with no exposure to water at all, or under the ocean. However, a small fraction have isotopic values consistent with formation in rainwater. Notably, all of these within the studied sample date to two time periods: a narrow band around 3.4 billion years ago and from 3.9-4.02 billion years ago.

Today, the Jack Hills are a rocky and arid region, but on the early Earth most formed under oceans, while some supported freshwater lakes.

Image courtesy of Simon Wilde

Previously, the oldest geological record of a water cycle came from 3.2 billion years ago. Geologists were sure the cycle began long before that, but they couldn’t know how long ago.

“Around 2000, the big theory was that 4 billion years ago the Earth was completely dry,” Olierook told IFLScience. “It was a desolate landscape, the sky was orange, the ground was brown. Then in 2001 evidence of water more than 4 billion years ago was found. We didn’t know the composition, but it was exciting enough to change the paradigm.” This caused a complete reversal, with the general assumption that the entire Earth at the time was probably covered by a global ocean, with most of the small islands penetrating.

However, the work done by Olierook and his colleagues shows that, at that time, there must have been a land where freshwater lakes could have formed, otherwise any rain would have mixed with seawater without changing the isotopic ratio.

The fact that freshwater zircons are so rare may indicate that such land was not particularly abundant, but this only tells the story of one spot on the globe. “About 5-10 percent of the Jack Hills zircons are 4 billion years old or older,” Olierook told IFLScience. “The next highest proportion anywhere else is one in 10,000.” This, he admitted ruefully, “does prejudice our understanding of the early Earth.” Perhaps large dry areas existed half a world away at the time and have since been recycled through the mantle.

The absence of freshwater zircons before 4.1 billion years ago, or between the two periods, also does not prove that the earth did not exist at those times. It could just be missing from the limited sample the team had to work with.

Debate continues as to whether life emerged around hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the ocean, or in a “little warm pool,” as Darwin proposed. This work shows that both were present from the beginning to make either option possible.

The study is published in Nature Geoscience.